Hydraulic Engineering and Surface Stability: Practical Protocols for High-Performance Drainage Infrastructure

Guest Contribution

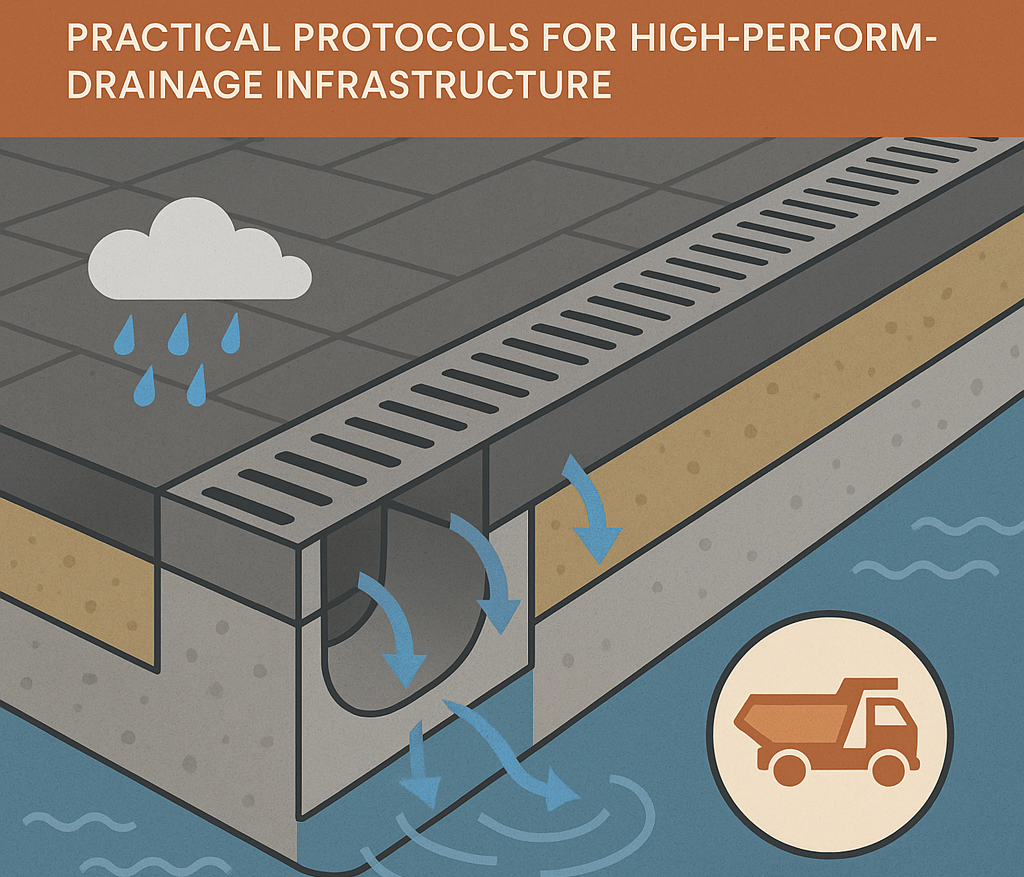

Modifying the natural terrain by installing impermeable surfaces—such as asphalt roadways, concrete logistics yards, or stone plazas—causes a dramatic shift in the local hydrological profile. By covering the permeable subgrade, these hardscape elements eliminate natural infiltration, forcing precipitation to travel horizontally as surface runoff. Without a rigorously calculated evacuation strategy, this displaced water accumulates in depressions, generating hydrostatic pressure that destabilizes the sub-base and weakens adjacent structures. In regions with pronounced temperature fluctuations, including Canada’s frequent freeze–thaw cycles, moisture within the pavement matrix expands when frozen, resulting in spalling, cracks, and deep-seated structural failures. Consequently, the long-term durability of any paved environment depends on integrating drainage infrastructure engineered to handle both hydraulic volume and mechanical stress.

When designers install a modern linear drainage solution—specifically a trench drain perpendicular to the primary hydraulic gradient—they intercept sheet flow along a continuous perimeter. This approach allows the pavement to be screeded on a single, consistent plane, maximizing the catchment area while simplifying the construction and leveling process. By contrast, traditional point-drainage systems rely on complex “pyramid” grade designs, where concrete must be sloped from multiple directions toward a central catch basin. These systems are labour-intensive, often produce uneven surfaces, and may create hazards for pedestrians and wheeled machinery.

The functionality of a drainage channel is defined by its ability to transport fluid without allowing suspended solids—such as sand, silt, and de-icing particulates common on Canadian surfaces—to settle. If flow velocity falls below a critical threshold, these solids accumulate and reduce hydraulic capacity. To prevent this, high-performance trench drains use pre-engineered internal slopes of 0.5% to 1.0%, generating gravitational acceleration toward the discharge point even where the pavement itself is level. On extended runs, engineers employ cascading systems in which channels of increasing depth (e.g., 6″ → 8″ → 10″) form an underground stepped profile, sustaining downward velocity while keeping surface grates flush with grade.

Structural failures in drainage systems frequently arise from a mismatch between the load rating of the components and the actual site traffic. The EN 1433 standard defines performance classes based on static and dynamic loads:

- Class A (15 kN) — Pedestrian areas, patios, walkways.

- Class B (125 kN) — Residential driveways; suitable for passenger vehicles.

- Class C (250 kN) — Commercial parking lots, delivery areas, light trucks.

- Class D–F (400 kN–900 kN) — Heavy-duty industrial zones, shipping terminals, airports, forklift routes.

Canadian conditions—heavy pickup trucks, winter tires, freeze–thaw stress, and road salt exposure—make selecting the correct load class essential.

The operational lifespan of any drainage installation depends heavily on material selection. Polymer concrete, used in many high-load trench drain systems, is non-porous, chemically resistant, and immune to freeze–thaw degradation. Its smooth interior surface ensures superior hydraulic flow. High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) is valued for its lightweight and impact resistance, especially in residential and pedestrian applications. However, due to its high thermal expansion coefficient, HDPE channels must incorporate external anchoring ribs to ensure permanent mechanical bonding with the surrounding concrete.

Proper installation plays a critical role in long-term performance. The drainage channel must be embedded in a concrete haunch providing 4–6 inches of support on all sides and along the base. This assembly distributes loads evenly into the subsoil. The grate should sit 3–5 mm below the surface grade to ensure efficient water capture and to reduce shear impacts from vehicle tires. On large concrete slabs, thermal movement requires expansion joints placed parallel to the drain to prevent cracking and structural displacement during temperature swings.

Trench drains are widely deployed across Canadian environments, including residential driveways, garage thresholds, commercial parking lots, logistics yards, patios, walkways, and public plazas. In all these settings, linear drainage systems mitigate water pooling, prevent ice formation, extend pavement life, and improve structural stability.

Conclusion

Effective surface water management is a discipline that combines hydraulic calculation with material science. By selecting components that withstand environmental stressors and following strict installation protocols—particularly regarding concrete encasement and expansion isolation—property owners can achieve long-term stability of their paved surfaces. Engineers must evaluate site conditions to choose the appropriate type of surface drainage system, ensuring consistent performance and safety.

For residential driveways, commercial parking lots, logistics facilities, or pedestrian environments, correctly choosing the trench drain and supporting infrastructure is essential. A deeper understanding of Types of Surface Drainage Systems helps property owners and engineers determine the most suitable solution for controlling runoff, mitigating ice formation, and ensuring long-term structural reliability in Canadian conditions.